A peppy series set in the early 1880s that’s loosely based on Italy’s first female attorney—who was much maligned by patriarchal forces—that’s jam-packed with murder most foul, deeply guarded secrets, and questions of the heart, and that is led by heroine who’s always pushing boundaries with a bounce in her step and a swear on her lips? Uh, yes, please! I’ll take one binge-watch. That said, do I also have some notes on privilege, the male gaze, and exceptionalism? Naturally.

We meet the attorney Lidia Poët as she’s engaging in some carnal pleasure with a Genetically Blessed gentleman friend (Dario Aita) who, much to the chagrin of both their pleasure centers, has to make a quick exit through the window when her landlady and the mother of an accused murderer come a-knocking at her door.

The woman’s son, whose mother swears is innocent, has been accused of killing a principal ballerina, stuffing her body in a trunk, and leaving it in a locked storeroom. Lidia, who is always a friend of the downtrodden and the dispossessed, and who also needs the money to pay her rent, takes the case. At the prison, she has to deal with the guard who makes what he thinks is a hilarious crack about her being a prostitute and then she must walk the gauntlet of imprisoned men hurling epithets at her. She meets her client, who convinces her of his innocence, though it’s unclear if he’s innocent of stalking the victim.

Lidia is fiercely determined and takes no shit from anyone. She even goes so far as to suggest that the judge on the case consider checking for fingerprints around where the victim was found. He and the prosecutor laugh at the idea of these new-fangled “fingerprints,” of which they’ve never heard. In addition to her knowledge outstripping that of her male colleagues, her attention to detail is keen, like when she goes to the morgue to look at the body, she notices small things that others have likely missed. Capability and femininity? You know that’s way too much for their masculinity, so the powers that be strip Lidia of her right to practice law, saying that “it is clear to the court that the Bar Association is an office in which women should not meddle.” They go so far as to call it unseemly that women argue in court and call into question the credibility of sentences decided on the merit of arguments made by women. This leaves Lidia—a fiercely independent woman who has, at great personal cost, sidestepped the trappings of marriage— penniless, vocationless, and with little choice but to move in with her brother Enrico (Pier Luigi Pasino) and his family. Enrico, who is also an attorney, is traditional, upright, and pretty prim, but she convinces (bulldozes) him into allowing her to be his assistant, with the caveat (a lie) that she will drop her appeal to get her license reinstated. Then she proceeds to foist upon him every wayward, seemingly hopeless client she finds, to stick her nose into every nook and cranny of the case after promising she will absolutely stay out of it, and then stitches those suckers up tighter than corset.

Also living in the house are Enrico’s wife Teresa (Sara Lazzaro ) and his teenage daughter Marianna (Sinéad Thornhill ), who will soon be presented to society, whether she likes it or not, which she doesn’t much, since she clearly idolizes her aunt’s freer spirit. On her first night with them, Teresa points out to Lidia that if God had wanted her to be a lawyer, he would have made her a man. To which Enrico readily agrees. So there you have the measure of the family, at least in the beginning. Because, as much as each ensuing case will impact the lives of the accused (and murdered, obviously), it will also serve as an opportunity for the Poët siblings to examine themselves, past and present, and to reevaluate their values and ethics based on the new information churned up in the course of the investigation. Murder as self-care, if you will. Not murdering as self-care, to be clear, just investigating already committed crimes as self-care.

Now, also in the house is Teresa’s brother Jacopo (Eduardo Scarpetta), a journalist with a Genetically Blessed face who drinks a lot, sleeps with many women, and seems to have ample time on his hands to tag along with Lidia to investigate crime scenes— kind of like a Watson who is also very interested in what lies beneath Sherlock’s undergarments. For yes, there is palpable sexual tension betwixt these two, even though he is guarding a very large and dark secret and she has an on-again, off-again dalliance with that other man, who wants her to consider leaving Italy. Or maybe better said, they have palpable sexual tension because of all those things.

Although I enjoyed all six episodes, the first two felt like the weakest to me because I worried they were laying out a pattern of exploitation of women’s deaths, objectification of women, and somewhat facile solutions to the murdery bits. I was glad to mostly be proven wrong by subsequent episodes, which added depth and nuance and which moved away from camera angles and shots that lingered and hungered for women’s mammarian mounds. You can talk all you want about women and equality, but the chips are really down when a bare-breasted woman wanders through a scene and we see what you do with the camera work. You know what I mean? I’m still somewhat confused by the upshot of the first episode and whether the innocent man did in fact stalk a woman (by modern day standards), and what it means that the show chose to not interrogate that at all or any further. And there is still the issue in a later episode of how they women housed in a mental hospital. Suffice to say, it wasn’t a good look. If your whole show is about demonstrating that the patriarchy is dead wrong about women’s abilities and capabilities, might you also question places that routinely locked women up simply for existing? Then there is the fact that as much as Lidia is exalted as vital and important and her work being vanguard of the women’s movement, she seems to be pitched as an exception. Don’t get me wrong here. I like Lidia Poët very much. What I take issue with, I suppose, is her uniqueness. The series doesn’t leave much room for the idea that there were other women trying to do the same thing. Or that there were other women equally as smart, but without the same resources to get as far ahead as Lidia. Perhaps I haven’t given them enough time to make that point, so I’m happy to be proven wrong. But there’s a scene about mid-way through the series that I found particularly troubling. Be forewarned, this explanation will contain some spoilers. In the course of successfully defending a woman who holds a doctorate in science (which, like Lidia’s law degree, is almost entirely unheard of) against a murder charge, Lidia uncovers the truth about a decades-old crime perpetrated against dispossessed women by men of science in the name of medical advancement. However, to expose this crime would mean also exposing the truth about her client, who has no family and would be remanded back to prison. Lidia urges her client to tell the truth, expose what these men have done, but also to admit to her own crime. Lidia insists that her admission will serve the greater good because these men’s long-ago crimes will finally be properly investigated and accounted for, and the remaining men properly punished. I’m sorry, what? I am, to put it mildly, aghast. This woman, who has no family, no money, no resources, no nothing, is now being asked to give up her freedom, for what? The hope that a bunch of flagrantly misogynistic and classist menfolk will investigate a years old crime for which most of the witnesses are either dead or prostitutes? Quite frankly, the likelihood of this kind of investigation getting buried and forgotten in the here and now is pretty fucking damn high. It just feels like a dangerously starry-eyed and privileged take they’ve given Lidia to foist upon her peer, and I don’t like it one bit. I don’t like that she doesn’t acknowledge her own privilege or resources. I don’t like that she’s asking a woman to give up her hard won freedom for some idealistic vision. Perhaps, it’s an accurate representation of who Lidia Poët was though, in which case I wish it hadn’t been shown here as such a noble gesture.

Something I do very much like is how they style Lidia to stand out against the background. In one scene her purple dress contrasts perfectly with the bright yellow of passing wagon’s wheels. Her eye makeup is always done with a single dot at the outer corners of her eyes, making them pop and appear somehow futuristic. She often has accessories in the shape of beetles or dragonflies or butterflies. The backgrounds of the scenes are rich and fun and carefully complementary, without overpowering the actors.

Overall, this is a fun and feisty series that weaves in mystery, family drama, romantic intrigue, women’s rights, Genetically Blessed Faces, and charming period costumes. Sometimes the murdery bits feel a little facile and sometimes the women’s rights bits feel a little under-explored, but neither to a burdensome degree, from a viewing standpoint. And it gets better and more layered the more you watch it.

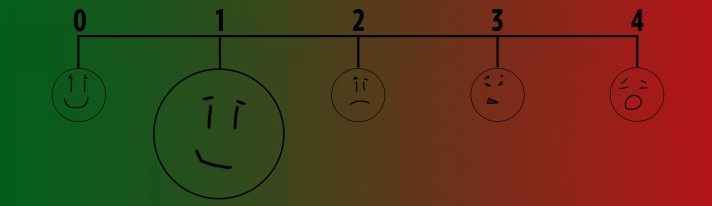

Overall Rating on the Chronically Streaming Pain Scale: